With almost 150 wineries in the region, the Finger Lakes American Viticultural Area (FLX AVA) is a wine region that I can continually return to. I did my first trip in 2019, and that only scratched the surface.

It’s almost certainly the best-known AVA on the east coast. Ancient glaciers widened existing river valleys, creating deep crevices that would eventually become the 11 lakes we know today.

These glaciers also left behind a diverse assortment of rock and soil. Old rocky soil is especially good for grape vines, as not only is it porous (vines don’t like wet roots) it forces grapes to struggle (struggling vines devote most of their energy into producing good fruit). These deposits of limestone, shale, gravel, and silt play a major role in the area’s ‘terroir’.

While soil is important, the lakes play an even more central role. These bodies of water act as temperature sponges, absorbing heat during the day and radiating it back to the shoreline at night. Without these lakes alleviating upstate New York’s cold weather, viticulture here would be far more difficult.

This combination of moderated weather and favorable soil creates excellent conditions for cool-climate grapes. The best vineyards are along the edge of these lakes, especially their deepest portions. Not coincidentally, this terroir is similar to that of the Mosel, Germany’s most famous riesling-producing wine region.

My 2019 trip was done with limited knowledge of where to go. This time I planned my trip more carefully, focused on select clusters of wineries around Seneca, Cayuga, and Keuka. Most of these tastings were drop-ins, but my parents & I also visited a number of reservation-only venues. We stayed at a long-stay residence in Watkins Glen, on the southern edge of Lake Seneca.

While our trip was centered around wine, I was happy to discover an assortment of non-alcoholic options were available. Many involved activities on lakes themselves, including kayaking and cruising. But my favorite non-winery excursions were hikes in local state parks, especially those that possessed waterfalls.

Over 5 days I visited 21 wineries. It sounds like a lot, but the tastings are often so slim that you can visit multiple locations and not get a serious buzz (and thank goodness for dump buckets). Nearly all the locations I visited had moved to a model of providing self-guided flights (often but not always pre-selected), but a few larger wineries took reservations for guided flights.

My greatest take-away was that riesling has far more range than I anticipated. The most enjoyable visits were locations that had wines from the same vintage but grown at different vineyards, each with their own terroir-driven personality.

It’s difficult to rank-order 21 wineries – especially since some days blended together despite my best attempts at note taking – so instead I sorted them in groups. Not coincidentally, my ranking system can be seen in how much wine I purchased (or not at all, in many cases) during a visit.

Except for the top 3 venues, wineries in the same tier are ranked about the same and listed in alphabetical order.

Being in a lower tier didn’t mean I didn’t like them. To the contrary, I can honestly say I didn’t visit any ‘bad’ wineries during my trip (I should note I also planned very carefully; no party-centric locations this time).

To be fair about my biases for what qualified as a higher-tier, I was specifically looking for riesling and sparkling wine, so red-focused wineries didn’t get rated as well as they probably should have been. My favorites tended to be smaller wineries where I had more personalized service; good wine was a bonus. Lower-rated locations often were at the end of the day, so no fault of their own I couldn’t enjoy their wine as much.

The Top Tier (#1-3) of my wine-visits are definitely listed in rank order. The downside to these particular wineries was all were in out-of-the-way locations or had limited visiting hours (and Kemmeter was reservation only). But they made up for that with not just outstanding wine but guided tastings which provided a significant educational component.

1. Kemmeter Wines (NW Seneca): This 6-acre vineyard was an amazing find. The tasting room is tiny and only open 3 afternoons a week (and closed Sundays). But I bought more wine here than at any other winery.

They are only open by appointment and have a maximum capacity of 6 guests. Yes – the tasting room is that tiny!

I enjoyed my visit so much I decided to write a separate blog so I don’t miss any details. Because of that I’ll keep this entry short.

Owner/winemaker/vineyard manager Johannes Rienhardt lead a tasting that consisted of 5 wines; a pair of rieslings (dry and off dry), a pinot, a pinot blanc, and a pinot rosé. I bought several of the dry rieslings and the rosé (which didn’t last the evening). The dry riesling was the best of the entire trip.

Johannes also had us play ‘guess the off-dry riesling’ and I guessed wrong. Turns out both were dry, although the one from the 2014 Vineyard could have fooled me. The two are grown on different types of soil and one location produces riper fruit. The density of the wine gives the illusion of sweetness. He fooled me but it was a great learning experience.

You can also order dumplings from his wife at their store outside; order first and pick them up later. Warning – they don’t have a public bathroom!

2. Forge Cellars (East Seneca): One of the smaller locations of my trip, with 40 acres of vines and a production of 10,000 cases/year. I loved the vineyard-specific rieslings (8 at this one place alone!), the view, and overall ambiance.

I highly recommend getting an appointment for a guided flight, which is as much about wine education as it is a wine tasting. But fear not, those who randomly drop-in can still enjoy a self-guided flight while sitting on the patio. They also had great cheese boards, plus excellent jamón.

Their “Classique” riesling is their best-known wine (and was definitely good) but it wasn’t my personal favorite of this visit. But I did leave with 2020 Freese (riesling) and 2020 Tango Oaks (riesling), both of which were among the best wines of my entire trip (right after Kemmeter).

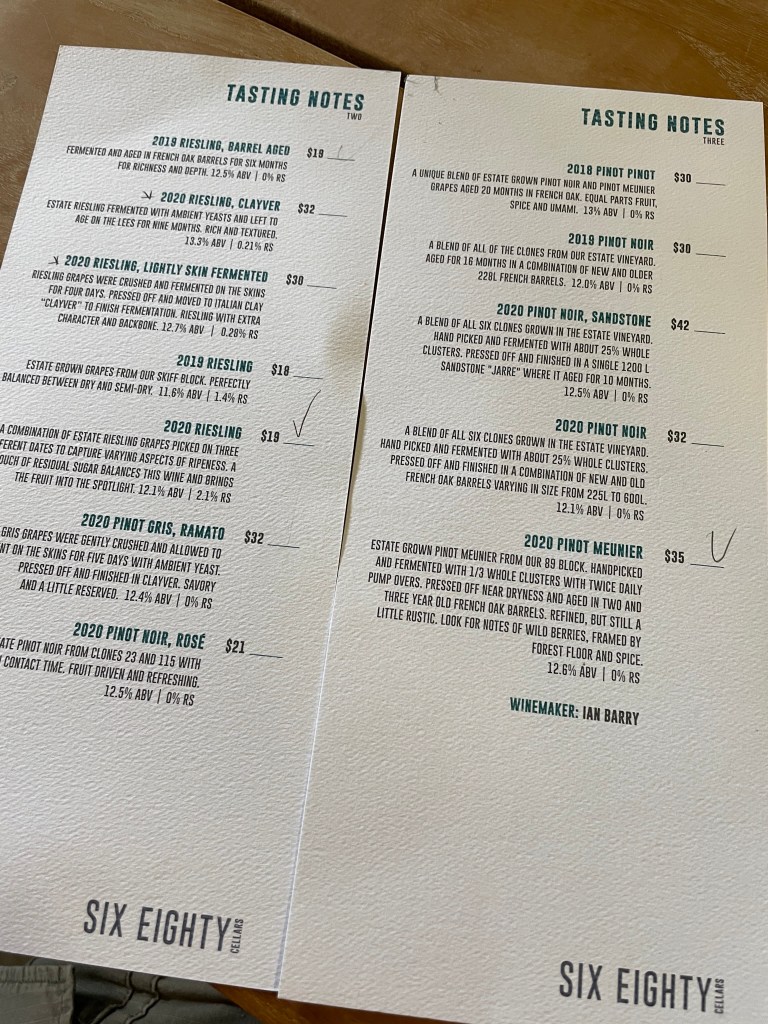

3. Six Eighty Cellars (West Cayuga): A very small (and brand new) producer with only 20 acres under vine. The wines were accompanied by light bites.

One thing that made them unique is their special focus on winemaking using a variety of fermentation vessels. They had your standard oak barrels and steel tanks, but they also had amphoras made of sandstone, clay, concrete, and terra cotta.

The small size of the winery meant we had very personalized service. Highlights included a mineral-driven 2020 Grüner Veltliner (made in a concrete tulip), an outstanding 2019 Riesling, and the flora, soft, and fruity 2020 Pinot Noir (made in a sandstone vessel). I left with some riesling.

My second tier (#4-7) wineries are ranked about equally. Every winery in this group had a solid lineup with several standout wines, and usually had other attributes (like food or service) that made it an overall excellent tasting experience. All are definitely must-try locations. All are in alphabetical order, not ranked in preference.

4. Hermann J Wiemer Vineyard (SW Seneca): One of the larger wineries in the area, with 131 acres under vine between HJW and their other property, Standing Stone Vineyards. HJW has their own estate vineyards plus they manage other people’s vineyard. They make around 35,000 cases/year between HJW and Standing Stone.

HWJ’s tasting experience is different from their neighbors in that they don’t have set flights. Every pour was separately charged, so you can get as many or as few as you want. My group didn’t have a tasting room associate with us, but it wasn’t overly busy so we still had lots of attention.

They had an excellent selection across the board, but my favorites were the 2020 Magdalena Cab Franc and an especially outstanding 2009 Cab Franc they brought out just for me. I wanted to like their biodynamic riesling, but just couldn’t get into it.

5. Heron Hill Winery (SW Keuka): This was one of the larger and lovelier venues of my trip. Heron Hill makes 30,000 cases/year, plus have 40 acres under vine between 2 vineyards. They also source fruit from elsewhere.

I admit I’m biased in describing this visit because it gave me a chance to catch up with a friend, winemaker Jordan Harris, who I knew from his time in Virginia. Jordan gave my family and I a very extensive tasting, including several not on the menu.

But my assessment of his 2020 Cabernet Franc and 2020 blaufränkisch needs no special boosting; both were excellent and I left with three bottles of the cabernet franc to show off to my Virginia friends (edit: one was enjoyed with dinner and another went home with mom for her birthday). Also shout-outs to the 2020 Pinot Noir (very fruit forward nose and easy drinking), his rosé, and the 2020 Chosen Spot red-blend.

6. Keuka Lake Vineyards (SW Keuka): One of the most underrated wineries in the area. So good that I made an exception and allowed myself a visit despite having been here in 2019.

Small to mid-sized by FLX standards, they have 40 acres under vine and make 2-3,000 cases/year. Three tasting flights were available, now served in an old barn. I went with the “Terroir Red” and “a mix of the “Terroir White”.

I LOVED their natural yeast vignoles pét-nat, which was the first wine I opened when I returned home. Their 2017 ‘Rows” dry riesling (complex, mineral driven, maybe lime notes), 2013 dry riesling (peach notes and honey, made with wild yeast), 2018 KLV Red (a table red with hybrids foch, vincent, and de chaunac, very good!), and 2019 cabernet franc were also excellent (some pepper, slightly fuller bodied than I often see.)

They also grow leon millet and make an orange wine. This is one of the few places where I genuinely enjoyed their wines made with hybrid grapes, which are rarely a favorite.

7. Weis Vineyards (East Keuka): Another rare repeat visit for me. It also helped that Dave McIntyre (wine writer for the Washington Post) was aghast at even the possibility I skip it. So back to Weis I went. Reservations recommended.

Weis has 40 acres of vines (mostly hybrids) but most of this estate fruit is sold locally. No word on the number of cases/year they make, but all of it uses locally sourced fruit.

My favorites included their 2021 Dry Riesling (nice and crisp), 2021 Wizner Select K (K for Kabinnet, more mineral-y and a tad sweet), and 2019 Merlot (great balance!). Also good were the 2020 Schulhouse red (an easy drinking blend of mostly Chancellor, plus 10% Cab Sauv, named in honor of the school house the tasting room now occupies), and dry rosé (nice balance).

I felt this tasting experience was more upscale than most other FLX locations. As for flights, out of 15 or so wines you can pick 5 but can order more. I liked this method since it was sort of a ‘build your own adventure’ style. We had a tasting room associate guide us through our wines.

The third tier (#8-13) had above average wines in all of them, and oftentimes they had great food, service, and/or an amazing view. All in this group are equally good and listed in alphabetical order, rather than ranked in any order.

8. Dr. Konstantin Frank Winery (SE Keuka): The granddaddy of Finger Lakes wineries. Guided tastings are by appointment only (and go fast, apparently), but you can also randomly visit and stay in their courtyard to enjoy a self-guided flight.

I go more into detail on their background (and the Finger Lakes in general) in my 2019 trip report so won’t repeat too much here. But suffice to say that any trip to the Finger Lakes is incomplete without a pilgrimage here.

“Dr. Frank” is one of the largest Finger Lakes wineries, making over 75,000 cases/year. While Dr. Frank has 60 acres under vine at their main estate plus 20 more acres at Seneca, most of their fruit is purchased locally.

This place has a large tasting menu, with all of their bottles being solid in quality and well-priced. I wasn’t personally moved to buy any particular bottle but I did especially enjoy their toasty Celeb (Sparkling Riesling) with brioche notes and their 2021 Dry Riesling.

Small dishes are also available.

9. Red Newt Cellars (SW Seneca): Mid-to-large sized winery. 20 acres under vine but another 100 leased. They make 24,000 cases/year, 1/3rd of which was devoted to their most popular wine, the off-dry ‘Circle’.

They were recommended to me because of their extensive collection of older rieslings. Multiple flight options were available, but I went with the Dry and Riesling flights. I think this is going to need a return visit since there was a lot left off the menu I never tried.

I really enjoyed their especially well balanced 2013 Dry Reserve (no saline notes, oddly enough) and the 2013 Bullhorn Creek, which was unusually for its spice and herbal notes. I noted how the Circle had a ton of action up front.

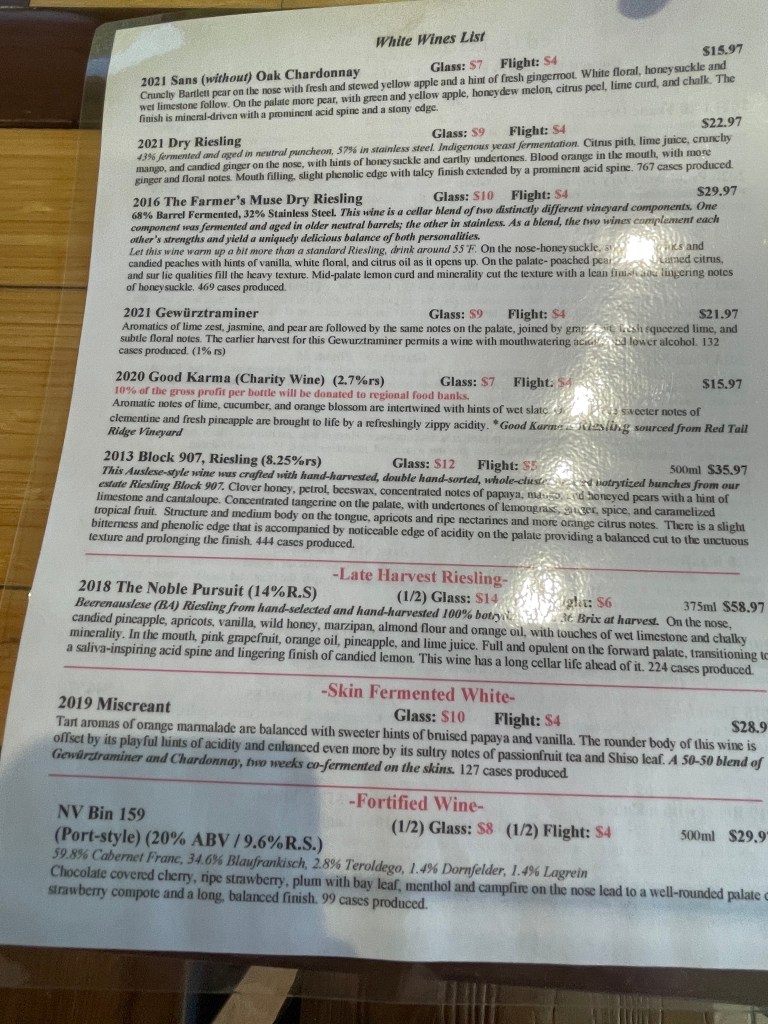

10. Red Tail Ridge Winery (West Seneca): A mid-sized location with 35 acres of vines planted. This includes several varietals you don’t often see including teroldego and lagrein, red grapes normally found in northern Italy. No notes on their production but was told its mostly estate.

I did the sparkling flight plus sampled a few others. Red Tail seemed to have one of the largest sparkling programs I encountered on the trip, and their pét-nats were especially good. The NV “Rebel With A Cause” (50% Terodego/25% Langein/25% Dornfelder) was probably my favorite, with the terodego red the runner-up.

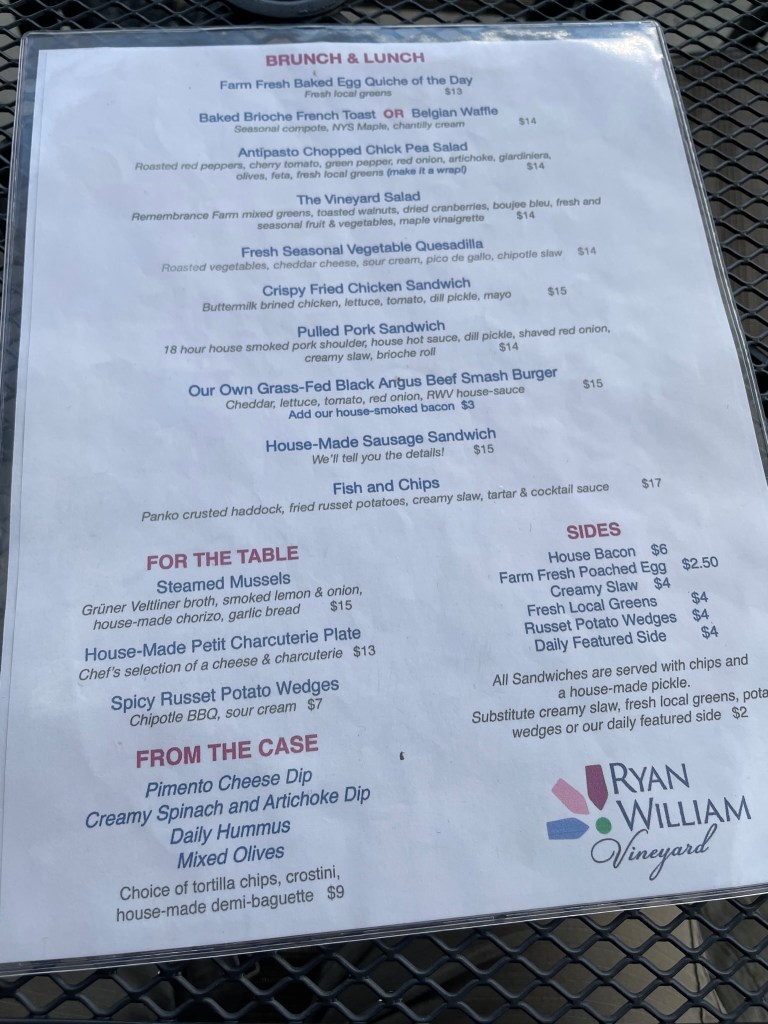

11. Ryan Williams Vineyard (SE Seneca): This was one of the larger wineries in the area. I didn’t get the number of cases they produce but was told they have 120 acres of vines. They also have a BEAUTIFUL tasting room with a great view of Seneca.

One standout element of my visit is they also have a full-service kitchen. Had I known I would have been brunching here all the time, although their lunch menu looked equally appetizing.

I tried the white and red flights, with my favorites being the very textured 2018 Chardonnay and soft 2017 Cabernet Franc. They also had a pretty good sauvignon blanc that was clean, fresh, and quaffable.

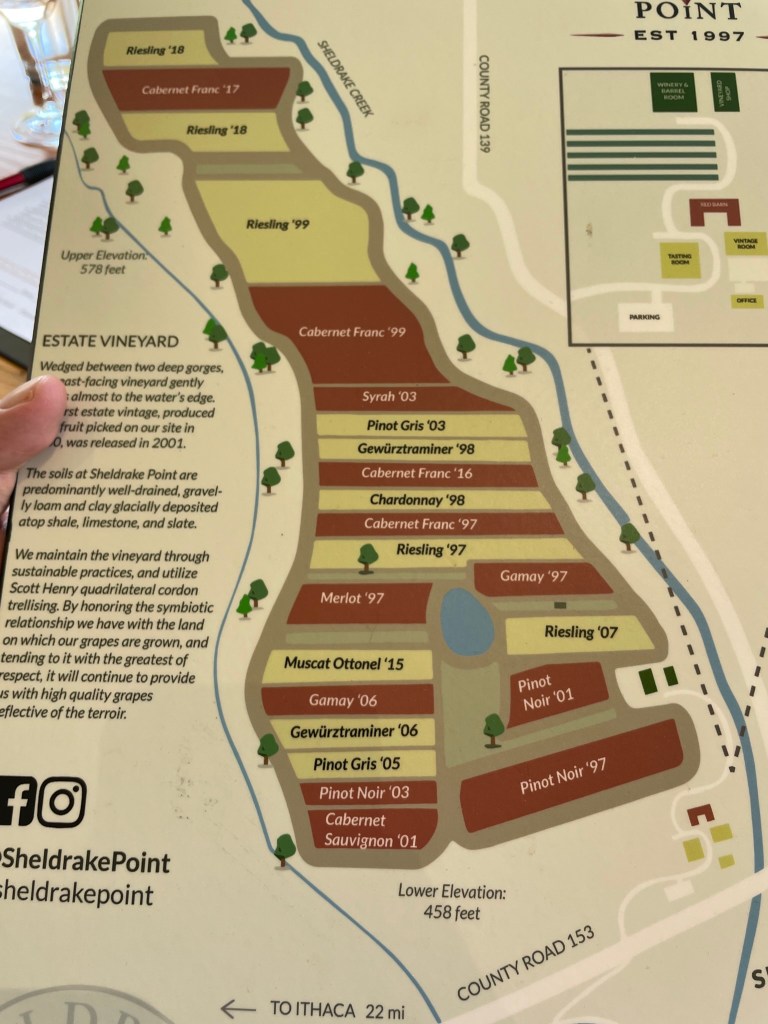

12. Sheldrake Point Winery (West Cayuga): An unexpected gem! Wineries along Cayuga are further away from the main tourist trail so they tend to be smaller, but this location stood out as a very classy venue with a lot of great wine and tasty light bites. The view and service were great.

Their wine is 100% estate, with 66 acres under vine. Ironically, they only make 7 or 8,000 cases/year (most of their fruit is sold).

My family and I shared three flights; ‘All about Aromatics’, ‘Cool Climate Reds’, and ‘Library Reds’. Favorites included the 2017 “BLK3” Pinot and 2013 Pinot, the latter of which was more tannic than I expected.

Mom said their 2012 Gamay (with 17% Syrah) was very much a ‘eat stake and put me to sleep wine’. I though the “Acid Head” riesling had an interesting sauv blanc quality to it, while the 2019 Reserve was very tropical, with notes of passion fruit.

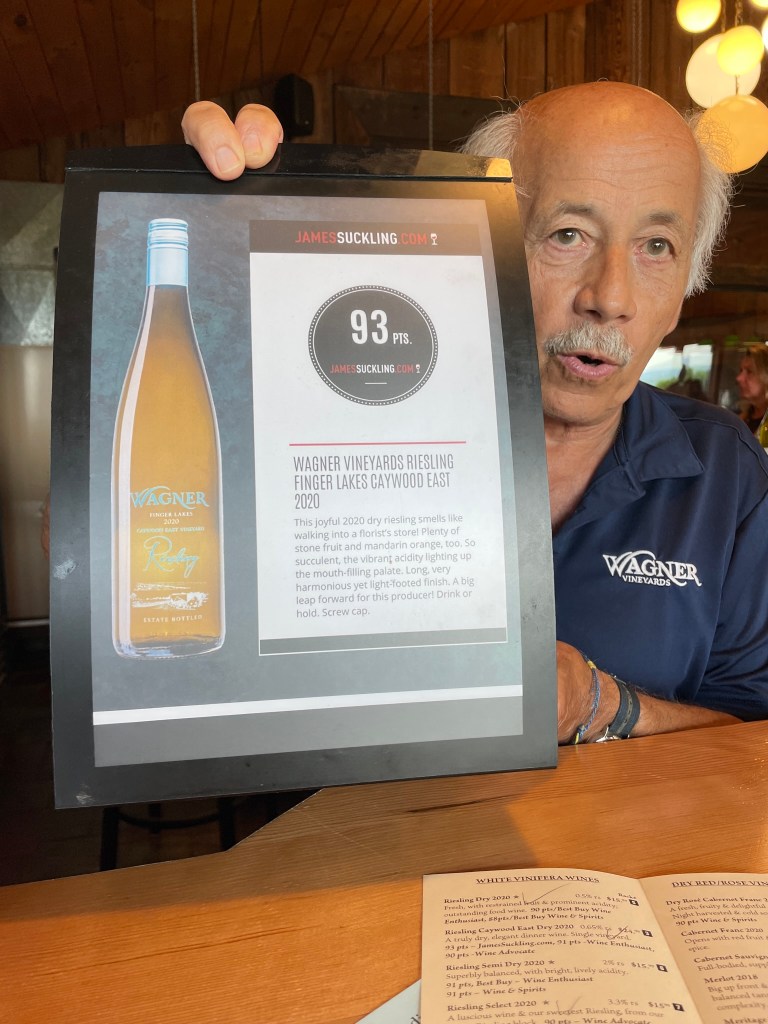

13. Wagner Vineyards (SE Seneca). Part of me wanted to be turned off by their large scale, commercial-winery vibe, but they won me over with great wine and service (and beer! and food!).

Wagner produces 60,000 cases/year and have 240 acres under vine, which makes them the largest grape distributor in the area. They have a very nice (and busy) tasting room as well.

I thought their 2017 Riesling was really good; minerally, light, and easy drinking. Apparently, Wine Enthusiast magazine thought so as well, since it chose this as one of their Top 100 affordable wines. The 2020 Riesling Caywood East Dry was my second favorite.

My fourth tier (#14-18) selections all provided pretty good wines. Some might have a standout I really enjoyed.

14. Atwater Vineyards (SE Seneca): While probably mid-sized by FLX standards, their 50-acre vineyard charges ahead with an exceptionally diverse vineyard consisting of 19 varieties. Among the hard-to-find vines planted are syrah and a bunch of hybrid grapes including reval (a hybrid of chardonnay).

This place should get an award for one of the nicest views of the trip. It’s not that far away from Watkins Glen, so I’d have totally hung out more here on a slow day.

No particular wine sang, but I did like their apple-note 2021 “Bubbles” sparkling riesling and 2020 Pinot Noir, which was made unfiltered and with minimal-intervention. I bought a bottle of the pinot just because it subverted my expectations of what a pinot should be like.

15. Fox Run Vineyards (West Seneca): This was a mid-sized location with 52 acres under vine and a production of 20,000 cases/year. They also had one of the best kitchens in the area, which by itself makes it a must-stop. The family and I enjoyed a great selection of sandwiches, salads, and personal pizzas.

The wine lineup didn’t disappoint either. My favorite was their Reserve Riesling (and I bought a bottle) but I also thought their “Silvan” Riesling was pretty good. Not sampled here, but back home I’ve also had a really nice meritage blend (not on the menu here, unfortunately).

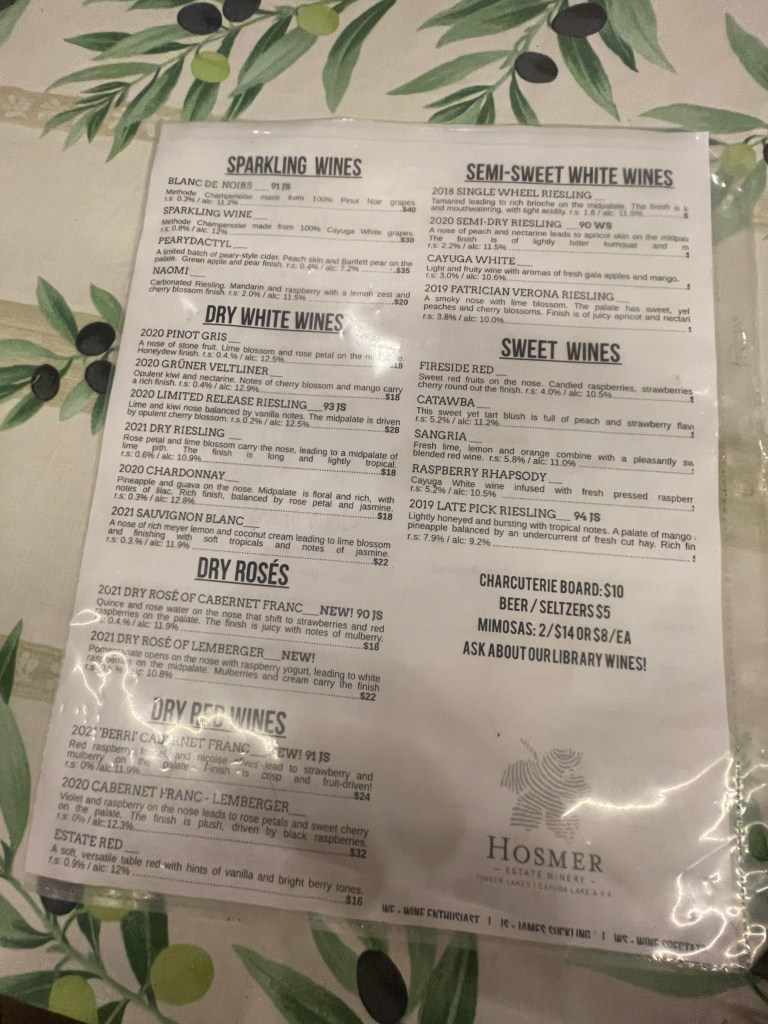

16. Hosmer Winery (West Cayuga): A mid-sized location, making 10,000 cases/year using 72 acres of grapes.

Hosmer is especially known for their dry reds plus their sauvignon blanc. They also have a petit verdot and lemberger (aka blaufränkisch), both of which were hard to find in this area. My favorite wine was a blend of cabernet franc and lemberger.

17. Ravines Wine Cellar (NW Seneca): This was one of my first visits of my trip and helped set the tone of the rest of the visit. Ravines is on the larger side at 30,000 cases/year from 4 vineyards, plus 130 acres under vine.

Several flight options were available, but my favorites were their dry sparkling riesling (which had a tad botrytis which made it interesting), plus their 2020 Cabernet Franc.

18. Shalestone Vineyards (East Seneca): I feel weird listing Shalestone so low because it’s definitely a nice place, and wine lovers who are red-focused would love it. It’s last in this group simply because of alphabetical order, and in a lower tier not because the wines aren’t well made but rather I wasn’t focused on reds.

When I asked why the focus was on reds, my server explained, “We only make wine we really want to drink”. They were also one of the smaller producers in the area, with only 6 acres under vine and a production of 1,200-1,500 cases/year.

That said their 2019 cabernet franc was one of the best in the Finger Lakes; aromatic with soft pepper notes. They also have a syrah and saperavi.

If you want to try some Finger Lakes reds – visit here first.

Last tier (#19-21) didn’t have any particular wines that tickled my fancy. In some cases, this was simply because they were unlucky enough to be the place I visited at the end of the day when my palate was tired.

19. Anthony Road Wine Company (West Seneca): They make 12,000 cases/year and have 100 acres under vine. I don’t have great notes on the visit, but I did notice the Devonian White blend (chard/riesling/pinot gris) and off-dry vignoles.

20. Magnus Ridge Winery (SW Seneca): Another winery on the larger end of the scale. It was unique in that they had cheese/food pairings with their wine flights. The most interesting combination was a traminette paired with wasabi.

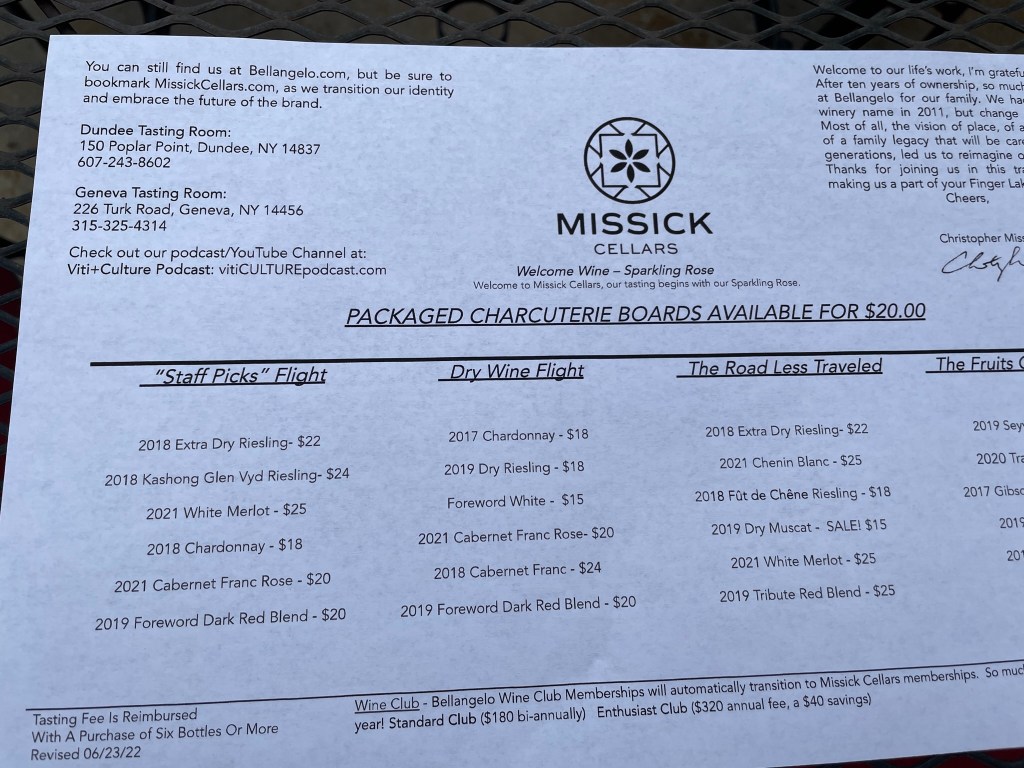

21. Missick Wine Cellars (West Seneca): Formerly known as Bellangelo, they rebranded a few years back when the new owner decided he wanted this place to be his legacy. They came highly recommended by Dave McIntyre of the Washington Post, so I had to try it. Missick makes 5,000 cases/year; not sure on the number of acres under vine.

Of the 4 flight options available I went with the “Staff Pick”, with chenin (!) as an add-on. At this point my wallet was in conservation mode, but I did think the ‘Foreword’ red blend made with 5 hybrids (foch, baco noir, marquette, dechaunac, chambourcin) was interesting enough to buy a bottle. It turned out to be my only purchase of a wine made with hybrids the entire trip.